Though many talks are interesting, once in a while there comes a talk in a graduate student's life that is so inspiring in both content and presentation. Today was one of these days. I attended the the "Intersectional Seminar Series" here at USC which is a seminar series meant to bring the different separate biology programs - Molecular and Computational Biology, Marine and Environmental Biology, Integrative and Evolutionary Biology and Neurobiology -together. Today's speaker was Bonnie Bassler from Princeton, and her talk title was "Eavesdropping on Bacterial Conversations". Today's blog entry is dedicated to the rich history of ideas she discussed in her talk. I apologize in advance to the longer than usual post and the higher than usual complexity as I try to accurately report back the ideas discussed in her talk.

To most lay people, the idea that simple, single-celled bacteria could use sophisticated means of communication may seem rather strange. But as early as 1979, Nealson and colleagues showed that a bacterial species with the name of Vibrio fisheri can communicate to other cells of each species to produce a light in a coordinated fashion. Vibrio fisheri are normally found in low abundance in almost all the world's oceans. The interesting thing is that these bacteria can detect each other. When the bacteria sense that enough of its brethren and sisters are around, all bacteria of that species start producing light. The picture to the left, taken from Science Daily, shows a flask of bioluminescent bacteria. Vibrio fisheri are also found living symbiotically within certain marine animals of the twillight zone (layer of ocean water receiving little light from 200-1000 m) where they are selectively captured and nurtured within the hosts "light organs" to serve many different purposes from blending with the environment, acting as an alarm system to serving to attract prey.

To most lay people, the idea that simple, single-celled bacteria could use sophisticated means of communication may seem rather strange. But as early as 1979, Nealson and colleagues showed that a bacterial species with the name of Vibrio fisheri can communicate to other cells of each species to produce a light in a coordinated fashion. Vibrio fisheri are normally found in low abundance in almost all the world's oceans. The interesting thing is that these bacteria can detect each other. When the bacteria sense that enough of its brethren and sisters are around, all bacteria of that species start producing light. The picture to the left, taken from Science Daily, shows a flask of bioluminescent bacteria. Vibrio fisheri are also found living symbiotically within certain marine animals of the twillight zone (layer of ocean water receiving little light from 200-1000 m) where they are selectively captured and nurtured within the hosts "light organs" to serve many different purposes from blending with the environment, acting as an alarm system to serving to attract prey.

How does Vibrio fisheri know how many other cells are around it?

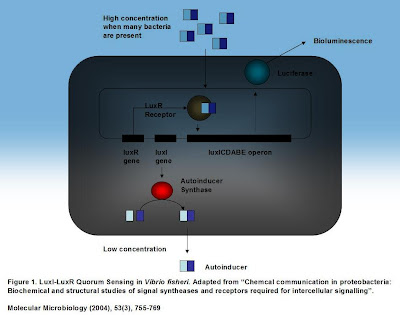

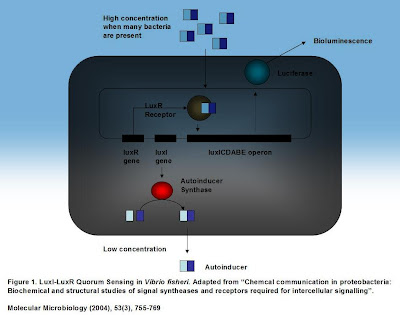

Two genes are responsible for this. The LuxI gene which is always expressed in Vibrio fisheri, produces a protein called Autoinducer synthase. This protein sythesizes a small molecule generally called the autoinducer which immediately diffuses out of the cell into the surrounding. For those interested, this small molecule is called N-3-oxohexacyl-l-homoserine lactone or OHHL for short. When there are very few bacteria around, the autoinducer leaves the cell too quickly to bind to the LuxR receptor, but when many surrounding bacteria are present, the concentration of the autoinducer increases. At some point, the concentration of the autoinducer reaches a point where the autoinducer cannot leave the cell quickly enough. Some autoinducer from the environment may even diffuse back into the cell. Another gene - the LuxR - gene produces the LuxR receptor protein. This protein can recognize the autoinducer and bind to it. Upon binding, the LuxR-Autoinducer complex activates transcription of a set of proteins that lead to bioluminescence. This is the way, the LuxI-LuxR gene pair works together to "sense" how many of its brethren and sisters are surrounding it.

Two genes are responsible for this. The LuxI gene which is always expressed in Vibrio fisheri, produces a protein called Autoinducer synthase. This protein sythesizes a small molecule generally called the autoinducer which immediately diffuses out of the cell into the surrounding. For those interested, this small molecule is called N-3-oxohexacyl-l-homoserine lactone or OHHL for short. When there are very few bacteria around, the autoinducer leaves the cell too quickly to bind to the LuxR receptor, but when many surrounding bacteria are present, the concentration of the autoinducer increases. At some point, the concentration of the autoinducer reaches a point where the autoinducer cannot leave the cell quickly enough. Some autoinducer from the environment may even diffuse back into the cell. Another gene - the LuxR - gene produces the LuxR receptor protein. This protein can recognize the autoinducer and bind to it. Upon binding, the LuxR-Autoinducer complex activates transcription of a set of proteins that lead to bioluminescence. This is the way, the LuxI-LuxR gene pair works together to "sense" how many of its brethren and sisters are surrounding it.

This concept is known in to biologists as quorum sensing. And what was thought to be an isolated occurance in Vibrio fisheri has now been found to be a common mechanism employed by many bacterial species. And the genes controled by LuxI-LuxR-like gene pairs have many different fucntions often having to do with biofilm formation and virulence in disease causing bacteria. The interesting part to note are two aspects. Each bacterial species has:

1.) its own LuxI-LuxR-like gene pair. They are similar but not the same.

2.) Each bacterial species has a very similar but very specific autoinducer. The autoinducer of one species is not recognized by another species.

A side remark: The discovery that LuxI synthesizes a homoserine derivative is in itself an exciting discover. The LuxI and LuxR gene pairs exist in different operons for different species. Operons are sets of genes that are always turned on or off together. One of the remarkable insights was to recognize the significance of finding the LuxI gene within a set of other genes responsible for the synthesis of threonine if my memory serves me right. Homoserine lactone is a metabolite meaning that it is generated as a product of metabolism. Two other enzymes are responsible for the first two step. The LuxI gene acts in the third step of the reaction.

What's the Take-Home Message?

In this first part, the LuxI-LuxR gene pair describes a system in which bacteria of the same species can release small chemical molecules as a means to specifically talk to members of their own species.

What's up next?

Next time, I will try to accurately summarize a system that potentially allows bacteria of different species to talk to each other in what Professor Bassler called "bacterial Esperanto".

Supplemental Sources:

For the writing of this blog, to ensure factual accuracy, in addition to the intersectional seminar, I was using the following source:

Pappas, K.M, Weingart, C.L, Winans, S.C. (2004) Chemical communication in proteobacteria: biochemical and structural studies of signal synthases and receptors required for intercellular signalling. Molecular Microbiology (2004) 53(3), 755-76.

http://animals.howstuffworks.com/animal-facts/bioluminescence.htm/printable

How does Vibrio fisheri know how many other cells are around it?

Two genes are responsible for this. The LuxI gene which is always expressed in Vibrio fisheri, produces a protein called Autoinducer synthase. This protein sythesizes a small molecule generally called the autoinducer which immediately diffuses out of the cell into the surrounding. For those interested, this small molecule is called N-3-oxohexacyl-l-homoserine lactone or OHHL for short. When there are very few bacteria around, the autoinducer leaves the cell too quickly to bind to the LuxR receptor, but when many surrounding bacteria are present, the concentration of the autoinducer increases. At some point, the concentration of the autoinducer reaches a point where the autoinducer cannot leave the cell quickly enough. Some autoinducer from the environment may even diffuse back into the cell. Another gene - the LuxR - gene produces the LuxR receptor protein. This protein can recognize the autoinducer and bind to it. Upon binding, the LuxR-Autoinducer complex activates transcription of a set of proteins that lead to bioluminescence. This is the way, the LuxI-LuxR gene pair works together to "sense" how many of its brethren and sisters are surrounding it.

Two genes are responsible for this. The LuxI gene which is always expressed in Vibrio fisheri, produces a protein called Autoinducer synthase. This protein sythesizes a small molecule generally called the autoinducer which immediately diffuses out of the cell into the surrounding. For those interested, this small molecule is called N-3-oxohexacyl-l-homoserine lactone or OHHL for short. When there are very few bacteria around, the autoinducer leaves the cell too quickly to bind to the LuxR receptor, but when many surrounding bacteria are present, the concentration of the autoinducer increases. At some point, the concentration of the autoinducer reaches a point where the autoinducer cannot leave the cell quickly enough. Some autoinducer from the environment may even diffuse back into the cell. Another gene - the LuxR - gene produces the LuxR receptor protein. This protein can recognize the autoinducer and bind to it. Upon binding, the LuxR-Autoinducer complex activates transcription of a set of proteins that lead to bioluminescence. This is the way, the LuxI-LuxR gene pair works together to "sense" how many of its brethren and sisters are surrounding it.This concept is known in to biologists as quorum sensing. And what was thought to be an isolated occurance in Vibrio fisheri has now been found to be a common mechanism employed by many bacterial species. And the genes controled by LuxI-LuxR-like gene pairs have many different fucntions often having to do with biofilm formation and virulence in disease causing bacteria. The interesting part to note are two aspects. Each bacterial species has:

1.) its own LuxI-LuxR-like gene pair. They are similar but not the same.

2.) Each bacterial species has a very similar but very specific autoinducer. The autoinducer of one species is not recognized by another species.

A side remark: The discovery that LuxI synthesizes a homoserine derivative is in itself an exciting discover. The LuxI and LuxR gene pairs exist in different operons for different species. Operons are sets of genes that are always turned on or off together. One of the remarkable insights was to recognize the significance of finding the LuxI gene within a set of other genes responsible for the synthesis of threonine if my memory serves me right. Homoserine lactone is a metabolite meaning that it is generated as a product of metabolism. Two other enzymes are responsible for the first two step. The LuxI gene acts in the third step of the reaction.

What's the Take-Home Message?

In this first part, the LuxI-LuxR gene pair describes a system in which bacteria of the same species can release small chemical molecules as a means to specifically talk to members of their own species.

What's up next?

Next time, I will try to accurately summarize a system that potentially allows bacteria of different species to talk to each other in what Professor Bassler called "bacterial Esperanto".

Supplemental Sources:

For the writing of this blog, to ensure factual accuracy, in addition to the intersectional seminar, I was using the following source:

Pappas, K.M, Weingart, C.L, Winans, S.C. (2004) Chemical communication in proteobacteria: biochemical and structural studies of signal synthases and receptors required for intercellular signalling. Molecular Microbiology (2004) 53(3), 755-76.

http://animals.howstuffworks.com/animal-facts/bioluminescence.htm/printable

Comments

Post a Comment